On September 27, 2018, the FCC released a declaratory ruling and report and order (available here). This post has been updated to reflect the FCC’s new regulations.

I. What are small wireless facilities?

A small wireless facility (sometimes referred to as a small cell facility) is a cellular network facility capable of delivering high transmission speeds but at lower ranges. Although they are called “small,” this is in reference to their small coverage area, not their physical size. These facilities, due to their heightened transmission speeds and capacities, are critical to the wireless industry’s deployment of 5G services. However, because a small wireless facility, when compared to a traditional macrocell tower, is only able to transmit data at low ranges and is not capable of transmitting through buildings and other structures, many more small wireless facilities are needed to cover the same geographic area that a single, traditional macrocell tower would cover. It is estimated that each wireless provider will need at least ten times as many small wireless facilities as macrocell towers to provide the same network coverage.[1]

II. Why are small wireless facilities in the public rights-of-way?

Wireless service providers and wireless infrastructure providers will seek to collocate small wireless facilities and construct wireless support structures in a municipality’s rights-of-ways for a number of reasons, but one of the primary reasons is that small wireless facilities require two resources: (1) data via fiber optic cable and (2) power, and both of these resources are often found in a municipality’s rights-of-way.

Additionally, many states have enacted statutes that, among other things, limit rights-of-way and permit application fees that a municipality can collect from a wireless service provider or wireless infrastructure provider and create statutory review periods for small wireless facility permit applications.[2] Often, utility poles and wireless support structures owned by private entities are exempt from these state statutes, further prompting wireless providers and wireless infrastructure providers to prefer to collocate small wireless facilities to existing municipal assets in the municipality’s rights-of-way.[3]

III. Which types of entities are collocating small wireless facilities or constructing wireless support structures?

In addition to traditional wireless providers, neutral host and other infrastructure providers are also expected to play a critical role in the deployment of small wireless facilities. Neutral host and other infrastructure providers will often lease their wireless assets to traditional wireless providers. As a result, your municipality might not receive any permit requests of applications for collocating small wireless facilities or constructing wireless support structures from traditional wireless providers such as AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint. Instead, your municipality may be receiving permit requests and applications from neutral host providers such as ExteNet and Mobilitie.

IV. Why should my municipality be concerned?

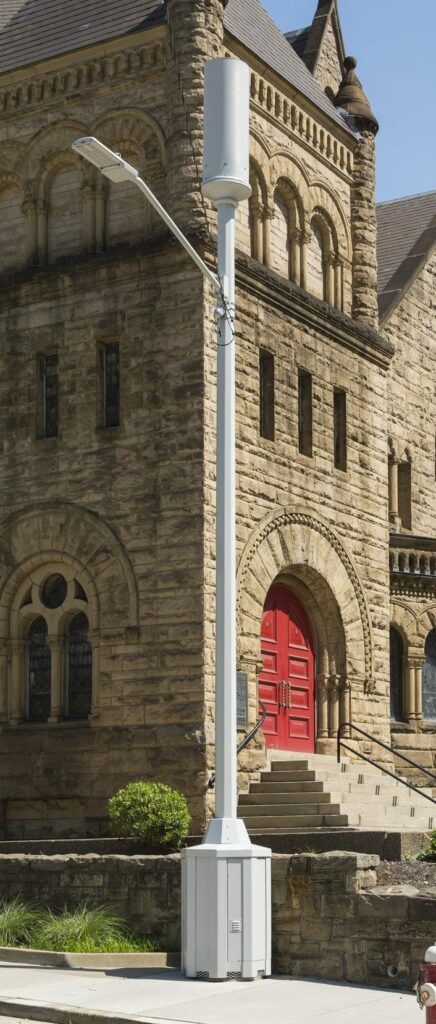

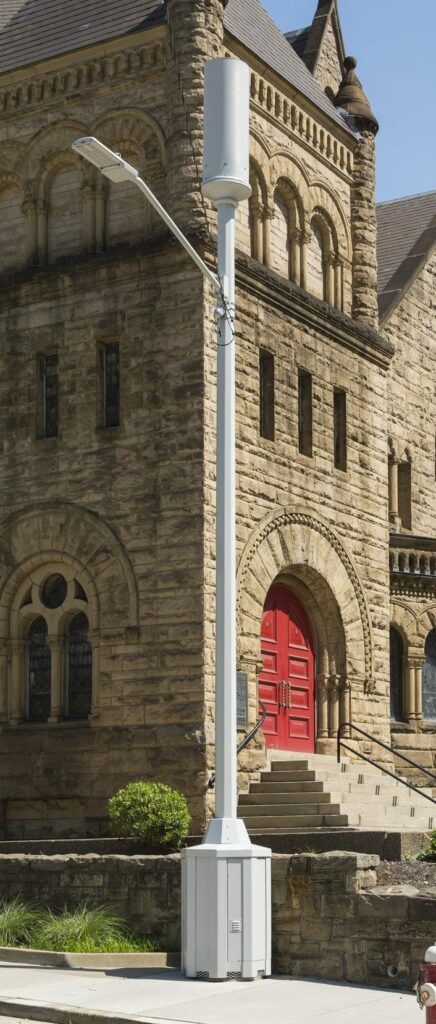

Not all small wireless facilities are created equal. While wireless providers and wireless infrastructure providers may initially propose to construct facilities that are integrated into light poles, monopoles, traffic signals, and other existing rights-of-way structures or assets, the reality is that your municipality should expect that very few small wireless facilities will be constructed in this manner. For example, a light pole with a pole-top antenna and integrated equipment cabinet is shown below. As can be seen in the below image, there are almost no exposed elements or cables, and there is only a minimal intrusion into the rights-of-way. The rights-of-way in the below image appears to be largely undisturbed by the small wireless facility integrated into the light pole.

Source: https://twitter.com/stealthsite/status/851882939633762304

However, in reality, many small wireless facilities are likely to be collocated on existing wooden utility poles. Because these existing utility poles are almost universally incapable of integrating equipment cabinets within the pole’s base, as is in the above image, wireless service providers and wireless infrastructure providers will instead install equipment cabinets at ground level or mount the cabinets to utility poles in the rights-of-way. These facilities can create safety, aesthetic, and noise issues, including violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (“the ADA”).

An example of a non-integrated small wireless facility is shown below. As can be seen in the below image, the small wireless facility extends beyond the wooden utility pole, the cabling is loose, and there are equipment cabinets mounted at the top of the pole.

Source: https://www.cleveland.com/middleburg-heights/index.ssf/2018/05/middleburg_will_closely_regula.html

These rights-of-way impacts and concerns are compounded by the increased number of small wireless facilities necessary to operate a small cell network. Regulating how and when small wireless facilities can be collocated in your municipality’s rights-of-way is key to addressing a municipality’s concerns such as safety, noise, aesthetic, and undergrounding of ground-level facilities.

V. How should my municipality respond to requests to collocate small wireless facilities or construct wireless support structures in its public rights-of-way?

When a municipality receives a permit request or application to collocate a small wireless facility or construct a wireless support structure, there are three sources of law that must be followed: (1) federal law, (2) state law, and (3) local law.

A. Federal Law

In 2018, the FCC issued a declaratory ruling and report and order addressing how municipalities must process small wireless facility applications.[4] A small wireless facility application is an application for a permit or other authorization that seeks to either: (1) collocate a small wireless facility on an existing structure or (2) collocate a small wireless facility on a new structure (i.e., construction of a new structure to collocate a small wireless facility).[5] The primary difference between these two types of small wireless facility applications is the number of days that a municipality is allowed to process the application (shown below).

| Type of Permit Request |

Review Period |

Remedy |

| Collocation on an existing structure |

60 days |

Judicial Cause of Action |

| Collocation on a new structure |

90 days |

Judicial Cause of Action |

If a municipality fails to grant or deny an application within either of these review periods, the applicant may appeal the municipality’s failure to act to an applicable court.[6] Unlike Section 6409(a) applications, there is no deemed granted remedy for small wireless facility applications.[7] A deemed granted remedy means that an application is automatically granted if a municipality fails to act on the application.

For more information on the details and impacts of federal law, please consult your legal counsel or the attorneys at Bradley Berkland Hagen & Herbst LLC.

B. State Law

After determining how to process a permit application or request under federal law, a municipality should next examine their state law. Often, state small wireless facility statutes will reduce review periods, limit the criteria by which a permit can be denied, and limit fees that municipalities can charge. A list of states that have passed small wireless facility laws can be found here. In short, state small wireless facility statutes are rarely, if ever, helpful for local governments. Instead, these statutes almost invariably limit municipal authority. For example, Oklahoma’s small wireless facility statute reduces the 90-day review period in federal law to 75-days and limits fees to $40 per small wireless facility collocated on a municipally-owned utility pole in the rights-of-way.[8] If your state has enacted a small wireless facility statute, it will be important to understand the restrictions and limitations placed on your municipality by state law in addition to federal law.

If your municipality is in a state that hasn’t passed small wireless facility-specific legislation, your municipality should nevertheless look for any processes or requirements that apply generally to wireless towers. These statutes were likely enacted with macrocell towers in mind but are often applicable to small wireless facilities.

C. Local Law

Finally, your municipality should examine its local law to determine how to process an application. Many municipalities have passed ordinances governing the municipality’s rights-of-way or wireless towers, but some municipalities have passed small wireless facility ordinances as well. While no small wireless facility ordinance “may prohibit or have the effect of prohibiting the ability of any entity to provide any interstate or intrastate telecommunications service” (i.e., a prohibition on the collocation of small wireless facilities within a municipality), these ordinances do allow a municipality to enact aesthetic and design standards, undergrounding requirements, and other zoning restrictions.[9]

If your municipality has not already enacted a small wireless facility ordinance, please speak with an attorney at Bradley Law, LLC to discuss how your community’s unique needs and interests can be addressed through an ordinance or other legal mechanisms.

[1] https://www.commscope.com/Docs/Powering_5G_Cell_Densification_WP-112370-EN.pdf

[2] https://www.smartworkspartners.com/state-legislation

[3] Collocating a small wireless facility means attaching a small wireless facility to any existing wireless support structure such as a utility pole or a building. Collocation is often confused to mean attaching a small wireless facility to an existing wireless support structure that already has a small wireless facility. This would imply collocation of the small wireless facilities themselves, but under federal law, it is the small wireless facility and wireless support structure that are being collocated.

[4] In the Matter of Accelerating Wireless Broadband Deployment by Removing Barrier to Infrastructure Investment, Declaratory Ruling and Third Report and Order, WT Docket No. 17-79 (Sep. 27, 2018).

[5] 47 C.F.R. § 1.6003(c)(1) (2018).

[6] 47 U.S.C. § 332(c)(7)(B)(v) (1996).

[7] 47 C.F.R. § 1.40001(c)(4) (2015).

[8] https://webserver1.lsb.state.ok.us/cf_pdf/2017-18%20ENR/SB/SB1388%20ENR.PDF

[9] 47 U.S.C. § 253(a) (1996). See 47 U.S.C. § 332(c)(7)(A) (1996).